https://youtu.be/lyWFshMVdjw?si=2IWBwzIkfWCD9Ve0

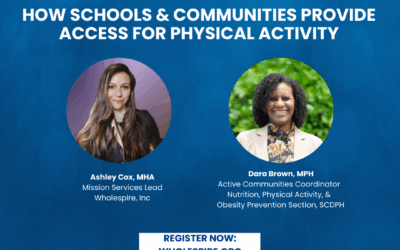

Built Environment

School & Clinical Linkages Through Docs Adopt

https://youtu.be/THeM6yiBFus

How to Get Fresh Fruits and Vegetables to Students

https://youtu.be/mIO8OZ2xEgg

Advancing Impact: Implementing Our New Four-Year Strategic Plan

A strategic plan is more than a roadmap—it is a living document that guides an organization’s direction, priorities, and decision-making. It reflects evolving challenges, opportunities, and community needs. As we launch our new four-year strategic plan, we embrace...

Healthy Palmetto Unveils Statewide Action Plan for Healthy Eating and Active Living

The newly launched Action Plan focuses on six strategic priorities developed through extensive collaboration among experts and community stakeholders.

Ruffin School: A Historic Landmark’s New Future

Find out how a local non-profit is turning the old Ruffin School into a community center and using a HEAL Mini-Grant to revitalize the baseball field.

SC State House Update: Bills are moving and new relationships are happening

We are actively engaged in advocating with our SC State House legislators to include health in all policies.

Inclusive Health Training w/ Special Olympics South Carolina

https://youtu.be/sO2Wj5ViUzE

Ashley Cox, MHS, NDTR

Mission Service Lead Ashley@wholespire.org