WIS TV Columbia

Wholespire-funded

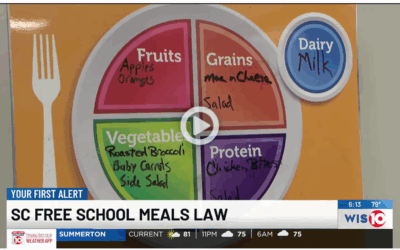

New law will help SC students access free school meals

WIS TV Columbia

How Schools & Communities Provide Access for Physical Activity

https://youtu.be/lyWFshMVdjw?si=2IWBwzIkfWCD9Ve0

School & Clinical Linkages Through Docs Adopt

https://youtu.be/THeM6yiBFus

How to Get Fresh Fruits and Vegetables to Students

https://youtu.be/mIO8OZ2xEgg

Advancing Impact: Implementing Our New Four-Year Strategic Plan

A strategic plan is more than a roadmap—it is a living document that guides an organization’s direction, priorities, and decision-making. It reflects evolving challenges, opportunities, and community needs. As we launch our new four-year strategic plan, we embrace...

Healthy Palmetto Unveils Statewide Action Plan for Healthy Eating and Active Living

The newly launched Action Plan focuses on six strategic priorities developed through extensive collaboration among experts and community stakeholders.

Ruffin School: A Historic Landmark’s New Future

Find out how a local non-profit is turning the old Ruffin School into a community center and using a HEAL Mini-Grant to revitalize the baseball field.

SC State House Update: Bills are moving and new relationships are happening

We are actively engaged in advocating with our SC State House legislators to include health in all policies.