Tips to consider when writing a Wholespire grant proposal

Funding your organization’s mission isn’t always easy, especially for non-profits. A lack of direct income means you often have to rely on external funding sources to support your work. This is a good opportunity where grants can help.

While working with a grant writer can help boost your chances of an application being funded, it isn’t always possible and organizations must then rely on their own staff. While grant writing is multifaceted, it’s very much a learnable skill. When people ask me to explain what I do as a grant writer, I’ve often replied that it isn’t rocket science, but organization and attention to detail are critical.

When people ask me to explain what I do as a grant writer, I’ve often replied that it isn’t rocket science, but organization and attention to detail are critical.

If you don’t have a lot of experience in developing grant proposals, here are a few tips to help your application stand out to reviewers:

Follow any formatting instructions provided on the application.

Pay attention to formatting specifications: Does the application ask you to use a certain font or to only submit as a PDF or Word document? Is the narrative (or any other section) supposed to be in paragraph style or bullet points? Is there a word count or other size limitation to your answers? Write as briefly and concisely as you can, and only give the information the application is requesting.

Describe your project in detail.

Arguably the most important part of a grant application is the project description. Ensure that you have narrowed your focus and that your project aligns with the mission of the funder. Projects that are too broad in scope will often not be funded because there either isn’t adequate time or money to successfully complete the project. Here are some things to consider when writing your project narrative:

- Why is the proposed project needed? What problem or opportunity will you address? Statistics and solid numbers will help enhance your proposal even more.

- How will you accomplish the proposed activities and objectives?

- Who will the project benefit? Be as specific with numbers and characteristics as you can, particularly if your project will serve disadvantaged groups such as low- to moderate-income, minorities, at-risk youth, or people with special needs.

- Is your proposed project part of a larger project? Many grants are used to move along or complete a larger project. Funders like knowing they are playing a part in a greater effort, but be specific in what phase of the project these particular grant funds will go toward.

Offer relevant background information.

Sticking to a 300-word limit project summary while also being specific is not a simple task. Other sections in the application, such as asking for information on your organization’s mission and activities, are where you can fill in the gaps and expand on details from the project summary. Here are some examples of helpful information to include:

- Demographics of the community being served.

- Project outcomes: how the proposed project will benefit the community or audience of focus and how you will measure your success.

- Sustainability: how will the project continue beyond the grant cycle?

- If applicable, a description of the larger project and what stage you are in.

Develop an accurate budget.

Most grants will maintain a maximum amount you can request in funding. Always make sure your budget falls at or below this number (unless you intend to fund the rest, which should be noted with a funds-commitment letter from the head of your organization). When putting together a cost estimate, it’s always better to have line items provided by a professional contractor, online pricing, or other verified means rather than figures you have assumed yourself.

Sometimes a funder may want to see your previous fiscal year’s organizational budget or bank statements to ensure you are operating at a profit and will have some available funds to continue your project. Be sure to include this information if requested.

Define community engagement efforts.

Community support of a project reinforces that a need exists within your area. Explain how input from your community led you to focus on this particular issue. This is also an appropriate section to describe key partnerships. What organizations and groups are you collaborating with, both by way of financial support and in-kind or volunteer efforts? How do you leverage other resources in the community?

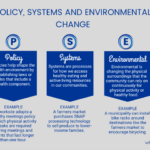

Most community coalitions conduct community health needs assessments to determine what’s important to community members and what they need most to lead a healthy lifestyle. Specifically for Wholespire’s mini-grants, use this information to prioritize policy, systems, or environmental projects and include it in the grant proposal.

Often times, your local government may also have administered a community needs assessment that you can request. If, however, an applicant does not have a needs assessment to rely on for direction, there are other ways to evaluate the community’s opinions and needs. Online surveys and community meetings are easy and low-cost alternatives.

Make sure to proofread!

Don’t let spelling and grammatical errors take away from an otherwise strong grant proposal. These types of careless oversights can lead to a reduction in scoring. Make sure to take advantage of spelling and grammar check tools before submitting your proposal.

It’s also a good idea to ask someone else to help you proofread your application. You’ve read through the application many times, so you may inadvertently skip over some errors or not have provided enough detail in a certain section. A second set of eyes could catch something you haven’t and can offer feedback to any clarifications needed.

Wholespire’s mini-grants (and non-profit or foundation grants in general) are very competitive, so give yourself enough time to write a quality application.

Wholespire’s mini-grants (and non-profit or foundation grants in general) are very competitive, so give yourself enough time to write a quality application. Reviewers can tell how much effort you put into your application and the proposed project by the information you submit. Allow yourself the time needed to submit your application prior to the due date.

Adrienne Patrick is the Director of Development at MPA Strategies, a statewide marketing and public relations firm. She is a certified Grant Writer and has successfully secured over $3 million in funding for MPA client projects including local infrastructure, non-profit programming, city planning, and community parks. Adrienne has years of experience in event planning and fundraising for both non-profits and political candidates, including serving as Governor David Beasley’s Finance Director for his United States Senate Campaign. She is a journalism graduate of the University of Georgia.