Why is community feedback an important piece of PSE change?

Change can be difficult for many people to accept, especially when they are unaware of the plans to create change or have not been asked for their input. By not involving the people impacted by the change, you risk alienating community members, losing support for future projects, and having less impactful project outcomes.

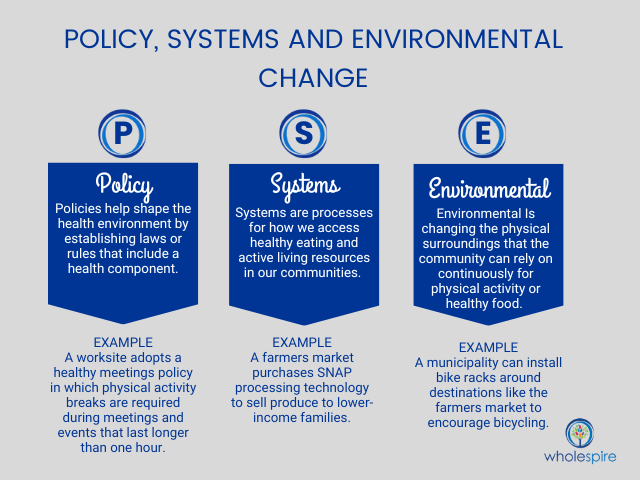

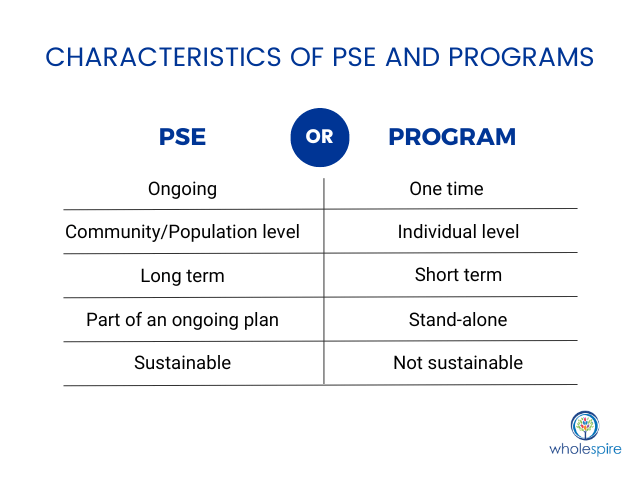

Community engagement, also referred to as feedback, input, involvement, or participation, means including community members in the decision-making, planning, and evaluation of projects. To ensure that projects and policies are relevant, successful, and long-term solutions, it is important to get the community’s opinions and active participation in the process. Community engagement is essential for policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) changes to effectively improve community health.

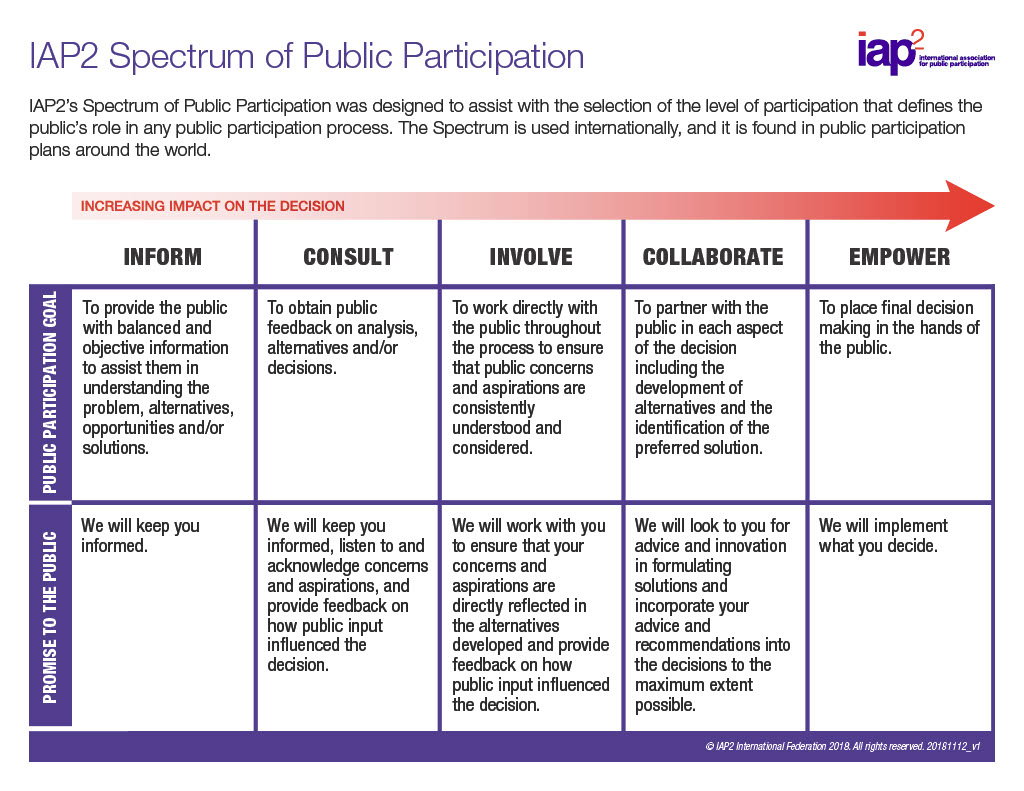

The level of community involvement can have a big impact on the success of your PSE project. The table below illustrates the range of community engagement. In the end, it is up to you or your coalition to decide how much community involvement you require or desire, as well as who to ask to participate. Wholespire suggests the following actions:

The benefits of community engagement

- Identifies community needs.

- Reinforces that a need exists.

- Identifies community leaders who can help overcome cultural and social barriers.

- Gathers community feedback from groups or individuals who are often overlooked.

- Increases the value of the PSE project.

- Drives equitable access to healthy eating and active living resources.

- Increases sense of community, empowerment, and inclusion.

- Creates the opportunity and openness for change and growth.

- Improves overall health outcomes

-

- Choose Consult, Involve, or Collaborate. These levels ensure community participation, drive equitable access, and make health outcomes more likely.

- Involve people who are often overlooked. It’s easy and convenient to invite the usual people you identify with. Be more inclusive by inviting community members from diverse backgrounds, especially those who will be impacted by the project.

- Listen to and incorporate the feedback. Listening to community members is great, but using their feedback is imperative. This step improves trust and morale and encourages future engagement and interest in community health improvement.

Most community health coalitions conduct community health needs assessments to determine what’s important to community members and what they need most to lead a healthy lifestyle. Oftentimes, your local health department or hospital may have administered a community needs assessment that you can request. If, however, a needs assessment is not available to rely on for direction, there are other ways to evaluate the community’s opinions and needs. Online surveys and community meetings are easy and low-cost alternatives.

Everyone plays a role in the health of their community. Get your community members involved in planning and implementing PSE change projects. They will point out obstacles and solutions that might not have been brought up before. And don’t overlook the younger generation. Who better to assist in making decisions about changes that affect them?